I was gazing north from the balcony of our hotel, the glowing lights of the town huddled at my feet. Far below, the Aegean stretched away through the night towards a lost horizon. Somewhere out there in the open sea lay the ancient, ruined island of Thera. What I did not know, as I turned and made my way back into the room, was that hidden beneath that island was a secret that was thousands of years old, a secret that would revolutionize my view of history. All of my ideas about history and world exploration were about to be turned upside down.

My wife Marcella and I had been looking forward to a quiet, contemplative Christmas, shut off from the world. After researching material for a new book I was dog-tired, so we decided to take a short break on the island of Crete. We would travel via Athens, one of our favourite places on earth. No more mobiles or email: we’d spend Christmas by candlelight in a former Byzantine monastery. Or so we thought. Our cosy dream of long walks through the classical ruins, followed by a week of Spartan simplicity in the mountains of Crete, was shattered when we arrived in Athens to find a mini riot in progress, right outside the hotel. In front of us protesting mobs of people milled around, shouting, waving placards and overturning cars. Police – bearing guns and wearing riot gear – stood menacingly in front of them.

So we took ourselves straight off to Crete, finding another spot, idyllic in its own way: a small hotel in the comfortable old Venetian port of Rethymno, in the north. Our first two days were marked by torrential downpours of rain. Then on Christmas Eve the rain lifted.

A few rays of sun turned into a soft mellow morning that beckoned us to explore beyond the snow-capped mountains we could see from our balcony. What we found that day put any thoughts of quiet, and of rest, out of the question: the discovery would set me on a determined hunt for knowledge around the globe.

We set out on a drive. In places, the narrow roads were more like fords, running with the past two days’ rain. As we drove rather gingerly through a muddy series of pretty villages, we could see that grapes still hung on the vine. The roadsides were carpeted with yellow clover and the fig trees still had their deep green leaves, even at Christmas. Crete is an incredibly fertile island. As we left one rickety village, we saw two men drag a pig across the road and string it up between two ladders, ready for slaughter. After a journey along winding roads, often blocked by herds of black and white goats, their bells tinkling to ward off snakes, we pitched up at our destination, picked that morning at random: the ancient palace of Phaestos.

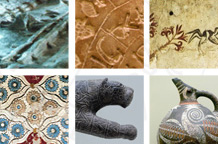

Myth has it that the city of Phaestos was founded by one of the sons of the legendary hero Hercules. It certainly looks majestic. The ruined palace complex unfolds like a great white plate on a deep green backcloth of pine forest to the south of the island. The ancient Greeks believed that this was one of the cities founded by the great king Minos, a mythological figure who reigned over Crete generations before the Trojan War. As we began to explore the ruins we quickly discovered that the symbol of Minos’s royalty was the labrys, or double axe, a formidable ceremonial weapon shaped like a waxing and waning moon, set back to back. The other symbol of Minos’s immense power was the terrifying image of a rampant bull.

We stepped out on to a ruin that was staggering. Phaestos is vast: bigger than the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne’s royal palace at Aachen, and at least three times the size of London’s Buckingham Palace. Its powerful but simple architecture is flawlessly constructed in elegant cut stone and it is laid out in what appears to be a harmonious plan. Wide, open staircases lead from the Theatre to the Bull Ring to the Royal Palace, and from there to smooth stone platforms that allow views of the ring of mountains beyond, the green plain sloping away to the distant sea. The overall effect was one of lightness and air. As the sun danced off the pools and courtyards, reflecting the azure sky, the whole site seemed like a mirage floating between heaven and earth. The serenity and scale of the place reminded us both instantly of the same thing: the monumental architecture of Egypt.

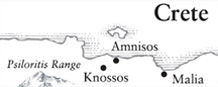

One other fact immediately gripped us. Like Knossos, its perhaps more famous sister complex further northeast of us, the palace at Phaestos is ancient. Older by far than the magnificent Parthenon in Athens, built c.450 BC when classical Greece was at its height – the people of Phaestos had lived in luxury and comfort more than a millennia before that. The palace is as venerable as the Old Kingdom of the pharaohs of Egypt and as ancient as the great pyramids of Giza. The site had been inhabited, we discovered, since 4000 BC.

This came as a real surprise to me. How was it that I had heard so little of this extraordinary but relatively obscure palace, whose beauty rivalled that of India’s Taj Mahal? What did I really know about the people who had built it: the people who are known as ‘the Minoans’? As we walked across the baking hot palace court, we realised that while most Europeans were still living in primitive huts, the ancient Minoans were building palaces with paved streets, baths and functioning sewers. Unparalleled for its age, the Minoans’ advanced engineering knowledge gave them a sophisticated lifestyle that put other contemporary ‘civilisations’ in the shade: they had intricate water piping systems, water-tight drains, advanced air-flow management and even earthquake-resistant walls.

We climbed a huge ceremonial stair, the steps slightly slanted to allow rainwater to run off. At the end of a narrow corridor we suddenly found ourselves in an alabaster-lined room. Here, a light-well struck sunbeams off the silent walls. These rooms, once several storeys high, were known as the Queen’s apartments, we were told. Phaestos’s rulers enjoyed stunning marble walls in their palaces: the people lived healthy and refined lives in well-built stone houses. Secure granaries kept wheat and millet safe from rats and mice and reservoirs held water all year round. The inhabitants enjoyed warm baths and showers – the men and women bathed separately – while their toilets had running water. Cut stone, expertly placed, lined the aqueducts that brought hot and cold water from the natural warm and cold springs which surrounded the palace. Terracotta pipes, built in interlocking sections, provided a constant supply of water, probably pumped via a system of hydraulics. All in all, what we saw before us was a more advanced way of living than in contemporary Old Kingdom Egypt, Vedic India or Shang China.

We duly bought Professor Stylianos Alexiou’s book, Minoan Civilization, for seven euros. As we looked through the text it became evident that in ancient times, as now, Crete was an island of magnetic attraction, the sort of place storytellers and poets would speak of with awe. This reverence had inspired potent legends, both about the place and the people who lived there. The head of the gods, Zeus, was said to have been born and died on Crete and it was here that another god, Dionysus, allegedly invented wine. In fact a large number of the ancient Greek myths I had learned at school had actually originated on Crete – their power so great that the tales have lasted for millennia. Epic sagas like those spun by the Greek poet Homer in the 8th century BC had been told at family firesides for centuries before that. In Book 19 of his Odyssey, Homer writes reverently about Knossos as a fabulous city lost in legend. After reading a little bit more about the Minoan civilisation, I realised that he was absolutely right.